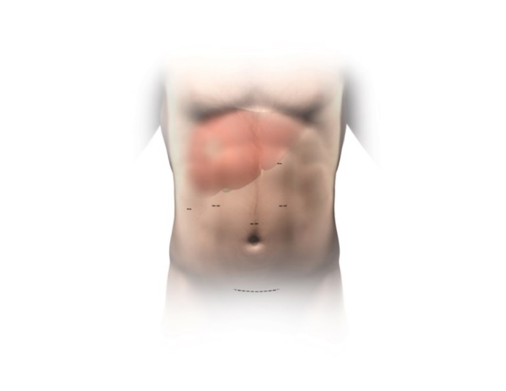

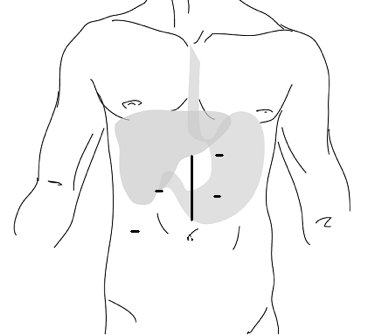

The donor surgery is called a partial hepatectomy, meaning "the surgical removal of a part of the liver." This surgery is most commonly used to remove benign or malignant liver tumors. Partial hepatectomy can be done safely, and partial hepatectomy in a well person carries less risk than when it is done to treat someone who is sick with liver disease. It is a major surgery, and there are still risks involved, including the risk of death.

With any major abdominal surgery, chronic pain, internal bleeding, infection of the wound or other organs of the body, and injury to other areas in the abdomen, as well as death, are potential risks. Other risks include postoperative fevers, pneumonia, and urinary tract infection.

Patients who have major surgery are also at risk to form blood clots in their legs. These blood clots can break free and travel to the lungs where they cut off the blood supply to a portion of the lungs. This is called pulmonary embolism. Blood clots in the legs occur in about 2% of all major surgeries; 2% of these blood clots will break off and cause pulmonary embolism. We try to prevent blood clots with inflatable sleeves that fit over your calves to keep blood flowing in the legs during surgery. When they do occur, blood clots and/or pulmonary embolism are treated with blood thinners that you need to take for several months and require you to have frequent blood tests. However, a large pulmonary embolism can be fatal.

Major abdominal surgery carries a risk of later bowel obstruction and/or pain due to adhesions. Adhesions are like scars in the abdominal cavity, which can form tight bands or make areas of intestines stick together and get twisted. Obstruction due to adhesions occurs in 5% of major abdominal surgeries and can occur years after the surgery. Sometimes adhesions can cause strangulation of the intestines and life-threatening gangrene. Obstruction from adhesions sometimes fixes itself, but often requires another surgery.

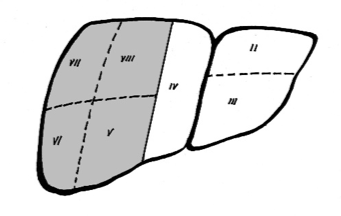

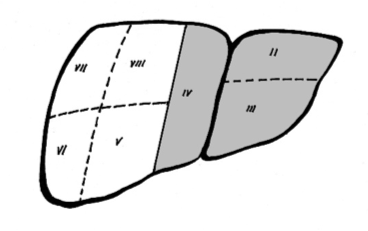

There are also risks that are specific only to this surgery. For the living liver donation, 25-65% of the liver will be removed. Removal of a portion of the liver may cause the remaining liver to not work as well for a short period of time, but it will soon recover and begin to grow back within a few weeks. However, in rare cases, liver failure can result and may require the donor to need a liver transplant. This is a very rare event (about 2 transplants per 1000 living liver donor surgeries). This has never happened at this center. If a living donor has liver failure and in need of a liver transplant they will be placed at the top of the liver transplant waiting list.

If you are having your right lobe removed, your gallbladder will also be removed during this surgery. The gallbladder is not needed for normal function. Some people who have their gallbladder removed have periods of diarrhea, cramping and intolerance to fatty foods, which may last for several months. Think of your gallbladder as a storage unit for bile which is produced in your liver and flows through bile ducts to your gallbladder. Bile is ultimately secreted to your small intestine help digest food. Without your gallbladder, bile will be secreted directly from your liver to your small intestine.

The most common liver complication after surgery is a bile leak. A bile leak occurs when one or more ducts from the liver have not closed entirely after surgery. Bile is irritating to the inner lining of the abdomen and can cause inflammation and scarring. Most bile leaks heal themselves, but occasionally a leak may require another tube to be placed through the skin to the liver to drain bile into a bag while the liver heals. In rare cases, surgery is required to close the leak. The rate of bile leaks happening across the country ranges from 5-15%.

A long-term complication that can occur is a biliary stricture which is a narrowing of the remaining large ducts that carry bile from the liver to the intestines. Early data shows that such strictures will be rare. They can usually be fixed without surgery by dilating the stricture with a stent (plastic tube) via an endoscopic procedure (through the mouth) or a percutaneous procedure (through the skin).

There are rare complications that can occur involving the blood supply to the liver, both in the arteries and veins. These include strictures and blood clots in these vessels that may occur long after surgery. The MRA or CAT scan that you have before surgery will help the donor surgeon to gauge how risky the surgery might be in this regard.

The most common late complication is the formation of incisional hernias. A hernia forms when the skin has healed, but the underlying muscles and connective tissue have not knit together well. This creates a bulge or "bubble" under the skin when standing. While this can be unsightly, more importantly, it has the potential to trap a loop of intestine and strangulate it, which can cause gangrene. For this reason, we often recommend surgery to correct hernias when they occur; in some cases, more than one surgery has been necessary. Hernias can occur in 5-7% of donors. If you are overweight, you may be more likely to develop a hernia. We believe that some hernias may be prevented by avoiding activities that put pressure on the abdomen, such as heavy lifting or straining at stool. The surgeon may place a mesh at the time of surgery to lower the risk of developing a hernia.

Nationwide, the risk of having some type of problem, minor or major, from this surgery is 15-30%. These include infection, hernias and swelling (about 2 in 7 cases). Most problems are minor and get better on their own. Rarely do they require another surgery or procedure.

So far in the United States, the mortality rate (death) has been about 0.2% or 2 deaths in about 1000 donors.

General Anesthesia

This surgery will be done under general anesthesia. There are a number of known possible risks with

any surgery performed under general anesthesia. An anesthesiologist will explain these to you in

detail.

Blood Transfusions

You may need blood transfusions during this surgery, although this is uncommon. The incidence of transfusion is about 1 in 100 cases.

Post-Surgical Course/Discomforts

Drains will be placed in your body to help you heal, to be removed before you are discharged from the hospital. There is a chance that you could be placed on a machine to help you breathe after surgery. You will feel pain (for example: gas pains, sore throat, soreness, backaches, etc.) after the surgery.

Regeneration

The success of living liver donation is partially due to the liver's natural ability to regenerate. Regeneration occurs rapidly in both the donor and the recipient. Even within the first seven days after surgery significant regeneration has occurred and within six weeks the liver sections in both the donor and recipient have grown to 80% of the size of a normal liver. However, growth then slows down and eventually stops, so that at one year the liver is still about 10% smaller than its original size. Liver function in the donor returns to normal levels within four weeks, with complete normalization of blood liver function tests by 12 weeks post-donation.