How old does my child need to be in order to receive a transplant?

There is no exact age that your child needs to be in order to be considered for a kidney transplant.

The timing of transplant depends on multiple factors that include your child’s age, weight, nutritional status, other medical conditions, and availability of a living kidney donor.

Our team assesses each pediatric patient individually and works to develop a plan that fits the needs of the child and their family.

I want to donate my kidney to my child – will my kidney fit?

As described above, each child is assessed individually to develop a plan. For potential living donors, the size of your kidney is just one factor that goes into our decision on the timing of your child’s transplant.

However, parents often serve as a living donor for their young children, so it is definitely possible to fit an adult-sized kidney into a child.

I want to donate to my child but I’m not compatible. What are our options?

The great news is that incompatibility really isn’t much of a barrier in kidney transplantation anymore.

Due to the widespread availability of kidney paired exchange, it is possible to find a compatible donor for your child, usually within a fairly short timeframe (several months).

As a founding member center of the National Kidney Registry, our transplant program is uniquely positioned to offer your child the opportunity for transplantation.

How much time will my child miss from school after their transplant?

Most patients are able to return to school or work within 3 months of their transplant surgery.

Of course, everyone’s recovery is different, so you will have to see how you are feeling as the time nears for you to make the decision to return to work or school. During this time period, your child will need to come for frequent visits to the hospital to monitor their new kidney and overall health.

For younger children who are enrolled in grades 1-12 in the five boroughs, your social worker will help in arranging home instruction with the NYC Board of Education.

If your child's school is outside the five boroughs, your social worker and doctor will write a letter to your school to inform them that they must arrange home instruction.

For older patients enrolled in college, if your child's transplant occurs during the school year, he or she may need to take a leave of absence or defer a semester. Your social worker can assist in writing a letter to your child’s academic institution.

We understand that having a kidney transplant during the school year disrupts your child's education. What should your child's teacher know?

Your Pediatric Nephrology and Transplant Team have put together letters to give to your child's teacher and other school officials to help them better understand the upcoming challenges that your child will face. We have also written a second letter to give to your other children's teachers because we understand that a transplant affects the entire family. Please contact your social worker for a copy of these letters.

What are the side effects of the transplant medications?

All medications may have side effects, and children may experience side effects differently than adults.

In general, medications that protect the kidney from rejection do so by suppressing your child’s immune system. This increases your child’s risk of infection and malignancy (cancer).

Medications can cause high blood sugar or diabetes; high blood pressure; electrolyte imbalance; skin changes; weight gain; nausea, vomiting or diarrhea; thinning of hair.

Why is a kidney transplant recommended?

A kidney transplant is recommended for children who have serious kidney dysfunction and will not be able to live without dialysis or a transplant.

In children, some of the most common kidney diseases for which transplants are performed include birth defects in the kidneys/genitourinary tract, familial/inherited disease, nephrotic syndrome, or systemic diseases such as lupus, hypertension or diabetes.

However, not all cases of those diseases require kidney transplantation. Always consult your physician for a diagnosis.

For the majority of patients, kidney transplantation offers better survival and better quality of life compared to remaining on dialysis.

How many children in the United States need a kidney transplant?

Currently, there are more than 95,000 people in total waiting for a kidney transplant in the United States. As of April 2018, there were 215 kids age 1 to 5 years waiting, 233 who are between the ages of 6 and 10, and 575 children between 11 and 17 years old.

You can visit the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) website for statistics of patients awaiting a kidney transplant, and the number of patients who underwent a transplant this year.

Where do transplanted organs come from?

Living Donors

Family members or individuals who are unrelated (spouses, friends, co-workers, neighbors, etc.) can donate one of their kidneys to someone who is in need of a kidney transplant.

In some cases, an altruistic donor (a person who wants to donate a kidney but has no specific recipient in mind) may be a donor.

These types of transplants are called living donor transplants. Individuals who donate a kidney can lead healthy lives with the kidney that remains. Visit the Living Donor Kidney Center section of our website to learn more about living donation.

Deceased Donors

Many kidneys that are transplanted come from deceased organ donors. This type of transplant is called a deceased donor (formerly known as cadaveric) transplant.

Deceased organ donors are people who are brain dead and cannot survive their illness and had previously made the decision to donate their organs upon death (by signing up at their local Department of Motor Vehicles or by joining a state or national donor registry). Parents or spouses can also agree to donate a relative's organs. Donors can come from any part of the United States.

There are different types of deceased donors, and it is important to understand the differences between the types because you will need to decide whether or not you are willing to accept a transplant from certain types of donors for your child.

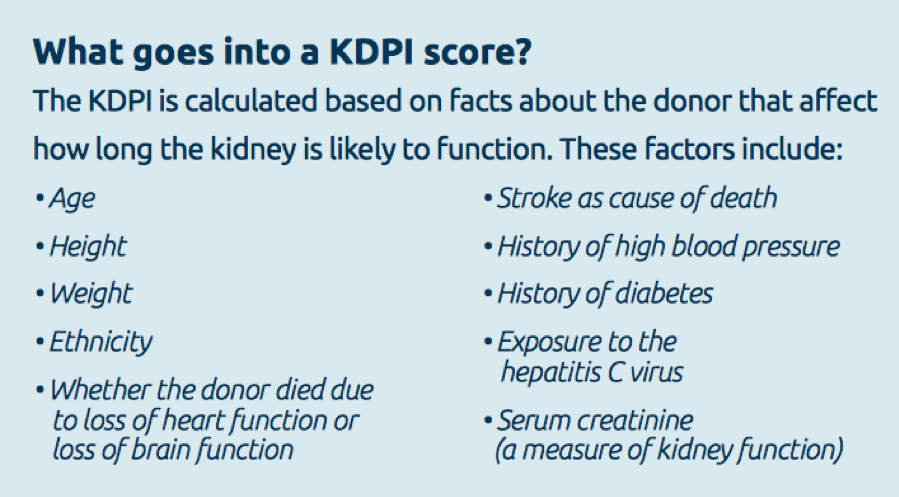

Each donated kidney has a Kidney Donor Profile Index (KDPI) score. This is a score from 0-100 that is calculated based on 10 factors about the donor. The score measures how long the kidney is likely to work. A lower KDPI is better.

• Low KDPI Score (<20): A low KDPI (under 20) means the kidney is from a donor who was younger and healthier when they died. A kidney with a KDPI score of 20 means it is likely to work longer than most (80%) of other donor kidneys. These kidneys typically last 10-15 years. Patients who receive a low KDPI kidney are usually the youngest and healthiest of the patients on the waiting list (including children), as these patients are expected to need a kidney that has the best capacity to last many years.

• Standard KDPI Score (20 to 85): These kidneys fall between the low and high KDPI kidneys. These kidneys typically last 10 to 15 years. These kidneys are sometimes given to children.

• High KDPI Score (over 85): A high KDPI score (over 85) means the donor was older or sicker when they died. These kidneys typically last 7-10 years after transplant. They are also called ECD (extended donor criteria) kidneys. We do not typically utilize these types of kidneys for children.

PHS Increased Risk Kidneys are another option for patients who want to get transplanted faster. PHS kidneys come from a donor who had a higher chance of having HIV or other blood diseases, such as Hepatitis C due to certain social behaviors (such as intravenous drug use or risky sexual behavior).

These kidneys typically come from younger, healthier donors, and usually last 10 to 15 years. PHS kidneys have a very slightly risk of an infection (less than 0.3%). Learn more about PHS increased risk donors.

When patients do not have any potential living donors, we recommend that patients discuss these special options with their transplant coordinator and physicians, as these kidneys are important opportunities for getting transplanted faster due to the ongoing severe shortage of organs available for transplantation.

How are transplanted organs allocated?

The United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) is responsible for transplant organ distribution in the United States. UNOS oversees the allocation of many different types of transplants, including liver, kidney, pancreas, heart, lung, and intestinal.

UNOS receives data from hospitals and medical centers throughout the country regarding adults and children who need organ transplants. The transplant team that currently follows you is responsible for sending the data to UNOS and updating them as your condition changes.

Criteria have been developed to ensure that all people on the waiting list are judged fairly as to the severity of their illness and the urgency of receiving a transplant.

For patients waiting for a kidney, organs are distributed based on waiting time, donor/recipient immune system incompatibility, pediatric status, prior living donor status, how far from donor hospital, and the survival benefit the patient may receive from that organ.

In addition, kidneys may be preferably given to patients who are a perfect match with the donor (which means that the genetic match is a 6 out of 6) because those kidneys are known to last longer than lesser matches.

Patients with very high antibody levels due to prior transplant(s), blood transfusion(s) and/or pregnancy may also receive priority when a good match is found.

When a donor organ becomes available, a computer searches all the people on the waiting list for a kidney and sets aside those who are not good matches for the available kidney.

A new list is made from the remaining candidates. The person at the top of the specialized list is considered for the transplant. If he/she is not a good candidate, for whatever reason, the next person is considered, and so forth. Some reasons that people lower on the list might be considered before a person at the top include the size of the donor organ and the geographic distance between the donor and the recipient. A negative crossmatch (where donor and recipient cells are mixed to make sure there is no reaction) is also needed prior to the transplant.

Is my child a candidate for a kidney transplant?

In order to determine whether your child may be a kidney transplant candidate, you should schedule an evaluation visit at our transplant center.

We cannot usually determine your child’s candidacy just by looking at their medical records. Some patients who look very sick on paper may be considered a candidate once you visit with the transplant center.

While dialysis center staff are very helpful about transplant education, they may not be very familiar with the requirement used at each transplant center. Therefore, it is best to come for an evaluation visit.

How is my child placed on the waiting list for a new kidney?

The first step is to be referred to our transplant center. Your child’s kidney doctor, primary care physician, dialysis unit, or other medical professionals can refer you. In addition, you can contact us to refer your child directly. Your insurance company may also have a list of preferred transplant centers.

Once you are referred to our program, we will ask you some basic questions over the phone and will then schedule you to visit us with your child for a pre-transplant evaluation.

This extensive evaluation must be completed before your child can be placed on the transplant list. Testing includes:

Blood tests are done to gather information that will help determine how urgent it is that your child is placed on the transplant list, as well as ensure that your child receives a donor organ that is a good match. Some of the tests you may already be familiar with, since they evaluate the health of your child’s kidneys and other organs.

These tests may include:

• Blood chemistries — These may include serum creatinine, electrolytes (such as sodium and potassium), cholesterol, and liver function tests.

• Clotting studies, such as prothrombin time (PT) and partial thromboplastin time (PTT) — tests that measure the time it takes for blood to clot.

Other blood tests will help improve the chances that the donor organ will not be rejected. They may include:

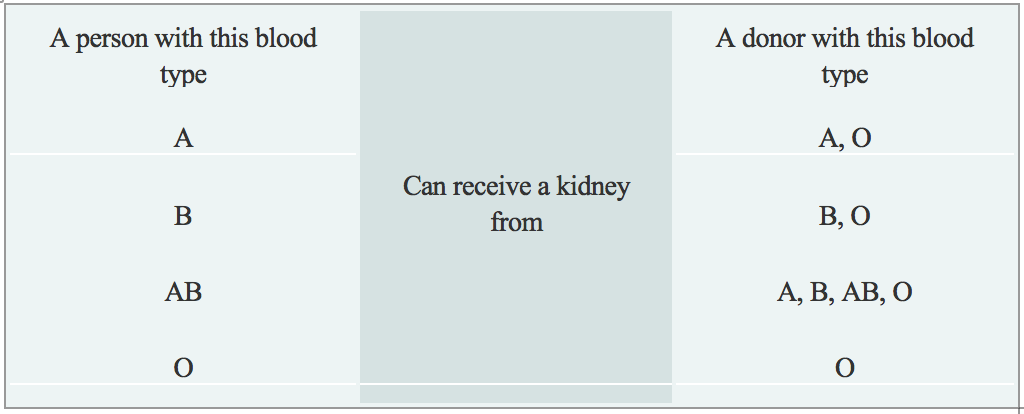

• Blood type: Each person has a specific blood type: type A, B, AB, or O. When receiving a transfusion, the blood received must be a compatible type with your own, or a reaction will occur. A similar reaction will occur if a donor organ of a different blood type is transplanted into your child’s body. These reactions can be avoided by matching the blood types of your child and the donor. The table below describes what blood types are compatible.

• In rare cases, transplants between a donor and recipient who have different blood types may occur by using medications to reduce the chance of a reaction. This is called ABO-incompatible transplantation.

• Human Leukocyte Antigens (HLA) and Panel Reactive Antibody (PRA): These tests help determine the likelihood of success of an organ transplant by checking for antibodies in your child’s blood. Antibodies are made by the body's immune system in reaction to a foreign substance, such as a blood transfusion, a virus, or a transplanted organ, and women may also develop antibodies during pregnancy. Antibodies in the bloodstream will try to attack transplanted organs, therefore, people who receive a transplant must take medications called immunosuppressants that decrease this immune response.

• Viral Studies: These tests determine if your child has been exposed to viruses that may recur after transplant and help us to tailor your child’s medication regimen after transplant.

Diagnostic tests that are performed are necessary to understand your complete medical status. The following are some of the other tests that may be performed, although many of the tests are decided on an individual basis:

• Renal ultrasound: A non-invasive test in which a transducer is passed over the kidney producing sound waves which bounce off of the kidney, transmitting a picture of the organ on a video screen. The test is used to determine the size and shape of the kidney, and to detect a mass, kidney stone, cyst, or other abnormality.

• CT Scan of Abdomen and Pelvis: A diagnostic medical test that produces multiple pictures of the inside of the body. These pictures show your child’s internal organs, bones, soft tissue and blood vessels in greater detail than traditional x-rays. CT scans are used to screen your child for infection, cancer, kidney and bladder stones, abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA), and to plan for your child’s transplant surgery by seeing their blood vessels in greater detail.

• Kidney biopsy: A procedure in which tissue samples are removed (with a needle or during surgery) from the kidney for examination under a microscope. Biopsies are sometimes used to determine the cause of your child’s kidney disease, which can be important since some kidney disease can recur in the transplanted kidney.

During the evaluation process, you and your child will meet with many members of the transplant team. The transplant team will consider all information from interviews, your child’s medical history, physical examination, and diagnostic tests in determining whether your child can be a candidate for kidney transplantation. After your child’s evaluation is complete and the transplant team believes that your child is an acceptable candidate for transplantation, your child will be placed on the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) waiting list.

Is my child allowed to be listed in more than one transplant center?

It is possible to be listed at more than one transplant center; this is called "multiple listing or multi-listing".

It is generally not beneficial to list at more than one transplant center within the local geographic region (and is not permitted in New York); therefore patients may list at different transplant centers in different geographic regions. You can click here to view a map of the different regions.

The United Network for Organ Sharing also has a section explaining multiple listing available on their website.

How long will it take to get a new kidney?

There is no definite answer to this question. Sometimes, children wait only a few weeks or months before receiving a donor organ,usually when a living donor is available to donate their kidney.

If your child has a blood type or crossmatch incompatible living donor, you may enter a registry to try to find a suitable match for your child and a suitable recipient for their donor's kidney.

If no living donor is available, it may take years on the waiting list before a suitable donor organ is available. Options such as choosing to accept an increased risk organ may help to reduce your child’s waiting time.

At Weill Cornell Medicine, we are proud that our innovative programs enable us to maximize use of available living and deceased donor organs, giving our patients a shorter waiting time compared to other transplant centers.

While your child is on the waiting list, you will receive close follow-up with your child’s physicians and the transplant team and you and your child will come back for a re-evaluation visit every year. Various support groups are also available to assist you during this waiting time.

Is living donation an option?

We all have heard about the shortage of organs available for transplantation. Unfortunately, the number of deceased donor organs has remained stagnant over the last several years, and this trend is expected to continue. As can be seen from the facts below, there is a great need to increase transplant opportunities for patients with kidney disease.

Although the 16,000+ kidney transplants performed each year in the United States may sound like a lot, the number is small compared to the number of people who are on dialysis, which is more than 650,000. It is also quite small when compared to the number of people waiting for a kidney (more than 95,000) and those never even referred for transplant evaluation (130,000+).

Given the high rate of complications and death while on dialysis, an increase in living donor kidney transplants holds the hope for improving the ability to transplant people who need a kidney.

Benefits of Living Donor Over Deceased Donor Kidney Transplantation

In addition to increasing the number of kidney transplants, living donation also provides the following benefits:

• Ability to schedule the transplant at a time that is convenient for both the donor and recipient helps to facilitate pre-emptive transplantation (transplant before the recipient needs dialysis), which is associated with better outcomes for the recipient

• Superior quality of living donor organs (as compared to deceased donor organs) leads to:

• Better function of the transplanted organ (immediate in the overwhelming majority of cases)

• Longer survival of the transplanted organ

How am I notified when a kidney is available for my child?

Each transplant team has their own specific guidelines regarding waiting on the transplant list and being notified when a donor organ is available.

In most instances, you will be notified by phone that an organ is available. You will be told to come to the hospital immediately so that your child can be prepared for the transplant. Even if you are called into the hospital, it does not guarantee that your child will receive that kidney; sometimes the kidney may go to someone higher on the list at another center. In addition, there may be a reaction when the donor's blood is mixed with your blood (called a positive crossmatch), which may indicate that your child should not receive that organ due to high risk of rejection.

What can I expect when my child gets a kidney transplant?

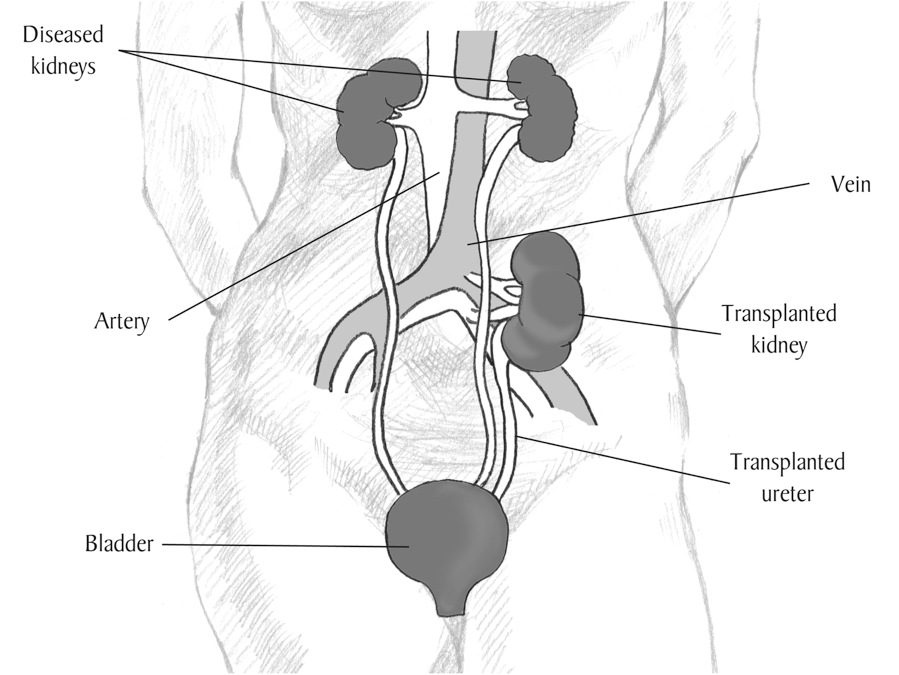

If all goes well and your child is designated to receive the kidney transplant, the surgery takes about 2 to 4 hours.

For pediatric patients with complex genitourinary anatomy, the surgery may take longer if the child requires urologic surgery at the same time as their transplant.

In most cases, the diseased kidneys are left in place during the transplant procedure, although some children require removal of one or both of their native kidneys at the same time as their transplant. The transplanted kidney is placed in the lower abdomen on the front side of the body.

Read more about the kidneys and how they work.

Image courtesy of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health

The transplant is performed under general anesthesia, and after the surgery, your child will be transferred to the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (ICU) for close monitoring.

Most children remain in the hospital for 4 to 7 days after their kidney transplant. Your child’s recovery period will consist of having his/her diet advanced, getting out of bed to walk, and participating in educational sessions with nurses, pharmacists, nutritionists, social workers, and others.

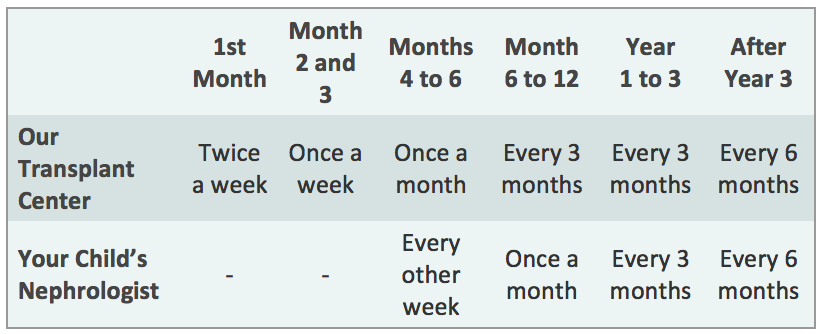

After your child is discharged from the hospital, you should expect to come back to the transplant clinic 2 to 3 times a week for the first month, then weekly for the next two months, then less frequently, depending on how your child is doing.

Your child will also be able to return to the kidney doctor who was caring for them before their transplant. We will work closely with your child’s doctor to manage their transplant, and you will continue to visit our Transplant Center periodically to ensure that your child’s kidney is functioning well, according to the schedule below. However, more frequent visits to the transplant center may be needed depending on your child’s post-transplant course.

What are the risks of kidney transplantation?

There are several categories of risks that may be seen with kidney transplantation.

The first are risks surrounding the surgery itself. These risks include side effects of general anesthesia; bleeding; blood clots; leaking or blockage of the ureter (tube that carries urine from the kidney to the bladder); infection; failure of the transplanted kidney to work; rejection of the kidney.

Other risks come from the medications that must be taken to prevent rejection of the kidney. These may include high blood sugar or diabetes; high blood pressure; electrolyte imbalance; skin changes; weight gain; nausea, vomiting or diarrhea; thinning of hair. Patients taking immunosuppression are also at higher risk for developing infection and cancer, particularly skin cancer.

What is rejection?

Rejection is a normal reaction of the body to a foreign object. When a new kidney is placed in a person's body, the body sees the transplanted organ as a threat and tries to attack it. The immune system makes antibodies to try to kill the new organ, not realizing that the transplanted kidney is beneficial.

To allow the organ to successfully live in a new body, medications must be given to suppress the immune system from attacking the organ for as long as the transplant continues to function.

If rejection does occur, it can be successfully treated in many cases, especially when caught early. This is why it is very important to take all medications as directed and follow-up with our transplant center as instructed.

Even if rejection does not cause the kidney to fail immediately, it can permanently damage the kidney and shorten its lifespan.

What is done to prevent rejection?

Medications must be given for the rest of the life of your child’s transplant kidney to fight rejection. Each person is individual, and the transplant team customizes your medication regimen to your child’s specific needs.

The anti-rejection medications most commonly used include:

Intravenous medications given in the hospital at the time of transplant:

• Rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin (Thymoglobulin) or

• Basiliximab (Simulect)

Oral medications taken for as long as transplant continues to function:

• Tacrolimus (Prograf or Advagraf or Envarsus XR) and

• Mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept)or mycophenolate sodium (myfortic)

Some patients may also receive one or more of the following medications, usually when they are at higher risk for rejection due to prior transplants, prior blood transfusions, and/or pregnancy:

• Prednisone

• Rituximab (Rituxan)

• Intravenous immune globulin (IVIG)

Usually, several anti-rejection medications are given initially. The doses of these medications may change frequently as your child’s response to them changes.

Because anti-rejection medications affect the immune system, people who receive a transplant will be at higher risk for infection. A balance must be maintained between preventing rejection and making your child susceptible to infection.

Blood tests to measure the amount of medication in the body are done at follow-up visits to make sure you do not get too much or too little of the medications.

This risk of infection may be higher in the first few months after transplant because higher doses of anti-rejection medications are given during this time. However, in the first few months after your child’s transplant, they will be given several medications to reduce the risk of certain types of infection.

What are the signs of rejection?

The following are some of the most common symptoms of rejection. However, each individual may experience symptoms differently. Symptoms may include:

• Decease in urine output

• Elevated blood creatinine level

• High blood pressure

• Fever

• Tenderness over the kidney

Your child’s transplant team will instruct you on whom to call immediately if any of these symptoms occur.

What is my child’s long-term outlook after kidney transplantation?

Living with a transplant is a life-long process. Medications must be given to suppress the immune system so it will not attack the transplanted organ. Other medications must be given to prevent side effects of the anti-rejection medications, such as infection. Frequent visits to and contact with the transplant team are essential. Knowing the signs of organ rejection and watching for them on a daily basis are critical.

You and your child will be the best people to inform us if your child is not feeling well or if something important (such as your child’s daily urine output) has changed dramatically.

Unfortunately, kidney transplants do not last forever. This is particularly important for our young patients, who may require several transplants over the course of their lifetime. Taking the best possible care of your child’s transplanted organ is important to reduce the number of future transplants that may be needed.

What happens if my child’s kidney transplant fails?

If a kidney transplant fails, the patient will need to return to dialysis. It may be possible to receive another transplant, however, this depends on many factors such as number of previous transplants, levels of antibodies in the body, and whether the patient was adherent to their medication and follow-up schedule.

In some cases, the new transplant can be performed before the previous transplant fails completely (particularly if a living donor is available) in order to avoid dialysis.