Whether you see us in-person or by Video Visit, we're here for you. See how we're keeping you safe.

Reflux is short for “reflux laryngitis” or “laryngopharyngeal reflux disease”, also abbreviated LPR. Digestive acid and enzymes flow upward from the stomach through the esophagus to the level of the vocal folds. This is the same process that causes gastroesophageal reflux disease, or GERD, except that otolaryngologists are preoccupied with its effects at the level of the larynx, instead of the esophagus.

Reflux is significant because the acid and enzymes that reach the larynx can cause injury and irritation. The larynx is not as well protected as tissues closer to the stomach, and thus, it has the potential to be more damaged by contact with stomach fluid. This may account for the phenomenon of “silent reflux”: reflux-related irritation in the throat without the more typical symptoms like heartburn or chest discomfort.

Irritation from reflux causes symptoms by itself, as well as contributing to other problems. It is a major factor in the formation of vocal fold granuloma. Ongoing research investigates reflux as a factor that compounds the effects of phonotrauma and smoking, and contributes to respiratory difficulties like asthma.

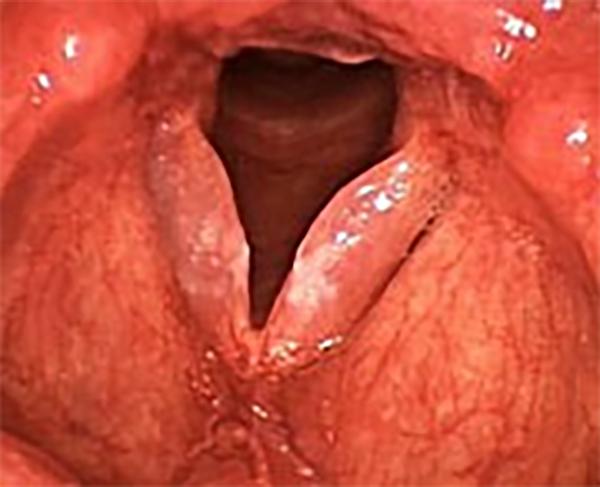

Severe redness and swelling of the vocal folds from a combination of smoking and reflux

Reflux causes irritation and swelling of the larynx. This can make it feel as if there is a mass or mucus in the throat. This has caused many to attribute the symptoms of reflux to “post-nasal drip”, a term with more meaning in advertising than in medicine. In fact, reflux is more common than irritation from nasal discharge.

Sometimes, an accompanying sensation, of tickling or pricking that triggers throat clearing or coughing, is present. Swallowing, particularly of dry solids, can become difficult. More severe reflux can cause throat pain and laryngospasm, a sudden involuntary closure of the vocal folds that makes it difficult to breathe for a few moments. People with reflux irritation typically cough and clear their throats constantly. During both of these actions, the vocal folds collide violently, and over time the chances of damage increase.

It is important to understand that the presence of the above symptoms does not necessarily mean that reflux is the main cause or even involved at all. Reflux may be only one part of a combination of factors contributing to the same constellation of symptoms.

Reflux-related irritation causes redness and swelling of the larynx, especially the parts close to the esophagus at the back of the vocal folds. Because such findings are so common in the general population, it has become clear that almost everyone occasionally experiences some reflux. The important clinical question is therefore not “Do you have reflux?”, but “Is reflux responsible for the problem which is bothering you?”

A milder case of reflux, with some swelling of the tissue at the back of the larynx and reddening of the vocal folds

Reflux is commonly related to irritative symptoms like cough, chronic throat clearing, or a foreign-body sensation in the throat. Reflux alone is rarely responsible for hoarseness, although it frequently aggravates the effects of nodules, polyps, or other lesions. As mentioned above, reflux is a major causative factor in granulomas.

Redness, swelling and thickening of the mucosa, involving the back of the larynx (top of image) and both vocal folds, can be seen in this case of a nonsmoker with severe reflux.

Based on typical findings, a provisional diagnosis of reflux may be made after examination of the larynx alone. However, because such findings are common and may also be caused by other factors, further testing is sometimes necessary. The acidity (pH) in the esophagus and the area around the larynx may have to be measured by means of a probe over a 24-hour period. The results of an esophagoscopy, in which a physician looks into the esophagus and stomach, are not particularly helpful for laryngeal disease, although they sometimes reveal reflux-related disease in other parts of the digestive tract. An X-ray study known as a barium swallow (esophagram) may reveal a common anatomic abnormality called a hiatal hernia, which predisposes a person to reflux.

It is not usually possible to “fix” reflux with medicine. It represents a problem that must be controlled through dietary measures and sometimes medication. Grease, fat and sugar tend to make reflux worse, as does alcohol, caffeine and nicotine. In addition to avoiding specific foods, it is important to eat smaller meals - and to eat earlier, at least three hours before lying down to sleep.

In more severe cases, particularly when there are nighttime symptoms, raising the head of the bed on bed blocks may be helpful. It should be noted that sleeping on several pillows or a foam wedge is not an adequate subsitution. In fact, this may make reflux worse by bending the torso and increasing pressure on the gut.

Medical treatment of reflux should be undertaken in conjunction with behavioral measures in order to be effective, and in consultation with a physician. The most powerful anti-reflux medications currently available are known as proton-pump inhibitors (e.g., Aciphex™, Dexilant™, Nexium™, Prevacid™, Prilosec™, Protonix™). Some of them are available without a prescription in a reduced strength. These are taken once or twice a day, 30-60 minutes before a protein-containing meal, which maximizes the effects of the drug. Reflux may also be treated with older, less-effective classes of medications known as H2-blockers (e.g., Zantac™, Tagamet™, Axid™) or common over the counter antacids (e.g., Tums™, Alka-Seltzer™, Mylanta™, Gaviscon™). Because reflux is a chronic problem, it may take several weeks to see a change in most throat symptoms. The relative advantages and disadvantages of medications should be discussed in detail with your doctor. Under no-circumstances should you continue to self-medicate more than two to three weeks without seeing your doctor.

In cases of severe reflux, surgery is available to correct a hiatal hernia, if it is causing symptoms. This is reserved for instances in which dietary measures and medication have not been effective.