What is a pancreas transplant?

A pancreas transplant is a surgical procedure performed to give a patient with type 1 diabetes mellitus a healthy pancreas from a deceased organ donor.

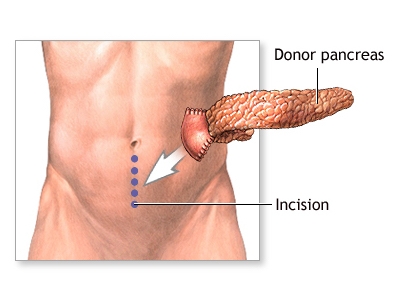

The diseased pancreas is left in place during the transplant procedure because even though it no longer produces insulin, it does still produce enzymes needed to digest the food you eat. The transplanted pancreas is placed in the lower abdomen on the front side of the body. When the transplanted pancreas functions well, patients are able to stop insulin injections immediately after transplant.

There are several types of pancreas transplant that can occur:

• Simultaneous pancreas and kidney transplant is performed in patients who also need a kidney transplant due to kidney failure from diabetes. The transplant is performed using organs from a single donor.

• Pancreas after kidney transplant is performed in patients who have already had a kidney transplant (usually from a living donor). The pancreas transplant usually occurs at least 6 months after the kidney transplant was performed, and the patient then has organs from 2 separate donors.

• Pancreas transplant alone is performed in patients who do not have kidney disease from their diabetes, but they do have other diabetes complications such as eye or nerve damage and hypoglycemic unawareness.

Why is a pancreas transplant recommended?

A pancreas transplant is recommended for people who have serious complications from type 1 diabetes mellitus. These complications may include kidney disease (nephropathy), nerve problems (neuropathy), decline or loss of vision (retinopathy) and/or are not able to sense when their blood sugar is dangerously low (hypoglycemic unawareness).

Pancreas transplantation is not a cure for diabetes, since patients need to take immunosuppressant medications to protect the pancreas from rejection. However, benefits of pancreas transplant may include ability to live without taking insulin injections, improved quality of life, and prevention or improvement in complications of diabetes.

How many people in the United States need a pancreas transplant?

Approximately 2,500 patients in the United States are waiting for a pancreas transplant (either pancreas alone of kidney-pancreas).

Visit the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) Web site for statistics of patients awaiting a pancreas transplant, and the number of patients who underwent a transplant this year.

Where do transplanted organs come from?

Most pancreas transplants that occur come from deceased organ donors. In rare cases, living donors may donate a portion of their pancreas, however this is not standard practice at most transplant centers.

Deceased organ donors are people who are brain dead and cannot survive their illness and had previously made the decision to donate their organs upon death. Parents or spouses can also agree to donate a relative's organs. Donors can come from any part of the United States.

How are transplanted organs allocated?

The United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) is responsible for transplant organ distribution in the United States. UNOS oversees the allocation of many different types of transplants, including liver, kidney, pancreas, heart, lung, and cornea.

UNOS receives data from hospitals and medical centers throughout the country regarding adults and children who need organ transplants. The transplant team that currently follows you is responsible for sending the data to UNOS, and updating them as your condition changes.

Criteria have been developed to ensure that all people on the waiting list are judged fairly as to the severity of their illness and the urgency of receiving a transplant. For patients waiting for a pancreas, organs are distributed based on blood type and waiting time.

When a donor organ becomes available, a computer searches all the people on the waiting list for a pancreas and sets aside those who are not good matches for the available pancreas. A new list is made from the remaining candidates. The person at the top of the specialized list is considered for the transplant. If he/she is not a good candidate, for whatever reason, the next person is considered, and so forth. Some reasons that people lower on the list might be considered before a person at the top include the size of the donor organ and the geographic distance between the donor and the recipient.

How am I placed on the waiting list for a new pancreas?

The first step is to be referred to our transplant center. Your diabetes doctor (endocrinologist), primary care physician, dialysis unit (if you also have kidney failure), or other medical professional can refer you. In addition, you can contact us to refer yourself directly. Your insurance company may also have a list of preferred transplant centers.

Once you are referred to our program, we will ask you some basic questions over the phone and will then schedule you to visit us for a pre-transplant evaluation. This extensive evaluation must be completed before you can be placed on the transplant list. Testing includes:

• Blood tests

• Diagnostic tests

• Psychological/social evaluation

Blood tests are done to gather information that will help determine how urgent it is that you are placed on the transplant list, as well as ensure that you receive a donor organ that is a good match. Some of the tests you may already be familiar with, since they evaluate your general health and organ function. These tests may include:

• Blood chemistries — these may include glucose, serum creatinine, electrolytes (such as sodium and potassium), cholesterol, and liver function tests.

• Clotting studies, such as prothrombin time (PT) and partial thromboplastin time (PTT) - tests that measure the time it takes for blood to clot.

• Diabetes-related tests, such as hemoglobin A1c, c-peptide levels, and antibody levels related to the diabetes autoimmune process

Other blood tests will help improve the chances that the donor organ will not be rejected. They may include:

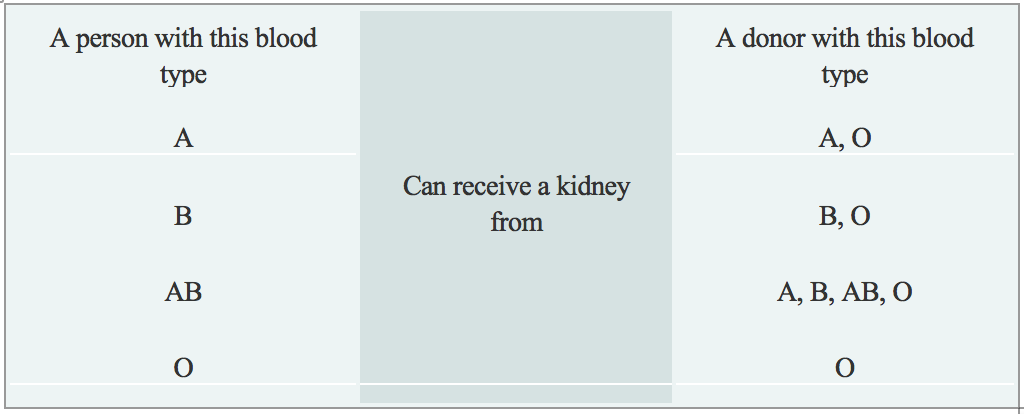

• Blood type: Each person has a specific blood type: type A, B, AB, or O. When receiving a transfusion, the blood received must be a compatible type with your own, or a reaction will occur. A similar reaction will occur if a donor organ of a different blood type is transplanted into your body. These reactions can be avoided by matching the blood types of you and the donor. The table below describes what blood types are compatible.

• Human Leukocyte Antigens (HLA) and Panel Reactive Antibody (PRA): These tests help determine the likelihood of success of an organ transplant by checking for antibodies in your blood. Antibodies are made by the body's immune system in reaction to a foreign substance, such as a blood transfusion, a virus, or a transplanted organ, and women may also develop antibodies during pregnancy. Antibodies in the bloodstream will try to attack transplanted organs, therefore, people who receive a transplant must take medications called immunosuppressants that decrease this immune response.

• Viral Studies: These tests determine if you have been exposed to viruses that may recur after transplant, and help us to tailor your medication regimen after transplant.

Diagnostic tests that are performed are necessary to understand your complete medical status. The following are some of the other tests that may be performed (if you also require a kidney transplant), although many of the tests are decided on an individual basis:

• Renal ultrasound: A non-invasive test in which a transducer is passed over the kidney producing sound waves which bounce off of the kidney, transmitting a picture of the organ on a video screen. The test is used to determine the size and shape of the kidney, and to detect a mass, kidney stone, cyst, or other abnormality.

• CT Scan of Abdomen and Pelvis: A diagnostic medical test thatproduces multiple pictures of the inside of the body. These pictures show your internal organs, bones, soft tissue and blood vessels in greater detail than traditional x-rays. CT scans are used to screen you for infection, cancer, kidney and bladder stones, abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA), and to plan for your transplant surgery by seeing your blood vessels in greater detail.

During the evaluation process, you will meet with many members of the transplant team. The transplant team will consider all information from interviews, your medical history, physical examination, and diagnostic tests in determining whether you can be a candidate for pancreas transplantation. After your evaluation is complete and the transplant team has determined that you are a suitable candidate for a pancreas transplant, you will be placed on the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) waiting list.

How long will it take to get a new pancreas?

There is no definite answer to this question. Sometimes, people wait only a few months before receiving a donor organ, however, it can also take several years on the waiting list before a suitable donor organ is available.

During this time, you will receive close follow-up with your physicians and the transplant team and will come in to our transplant center for yearly re-evaluation visits to make sure you are still a suitable candidate. Various support groups are also available to assist you during this waiting time.

How am I notified when a pancreas is available?

Each transplant team has their own specific guidelines regarding waiting on the transplant list and being notified when a donor organ is available.

In most instances, you will be notified by phone or pager that an organ is available. You will be told to come to the hospital immediately so that you can be prepared for the transplant. Even if you are called into the hospital, it does not guarantee that you will receive that pancreas; sometimes the pancreas may go to someone higher on the list at another center.

In addition, there may be a reaction when the donor's blood is mixed with your blood (called a positive crossmatch), which may indicate that you should not receive that organ due to high risk of rejection.

What can I expect when I get a pancreas transplant?

If all goes well and you are designated to receive the pancreas transplant, the surgery takes about 3 to 5 hours. It is performed under general anesthesia, and you will spend several days in the surgical intensive care unit after the surgery so that you and the function of the new pancreas can be closely monitored.

Check out the various steps of the pancreas transplant procedure by clicking here.

The majority of pancreas transplant recipients will have a nasogastric tube (a tube placed during surgery) that prevents too much pressure from building up in the intestines where the new pancreas is connected. Because of this, it will be several days before you are able to eat, and the majority of your medications will be given through your intravenous line (tube placed in your vein).

If you are doing well, you will be transferred to the Transplant Unit within several days of your surgery, and will likely be in the hospital for a total of six to eight days. Once on the transplant unit, you will begin your recovery period that includes having your diet advanced, getting out of bed to walk, and participating in educational sessions with nurses, pharmacists, nutritionists, social workers, and others.

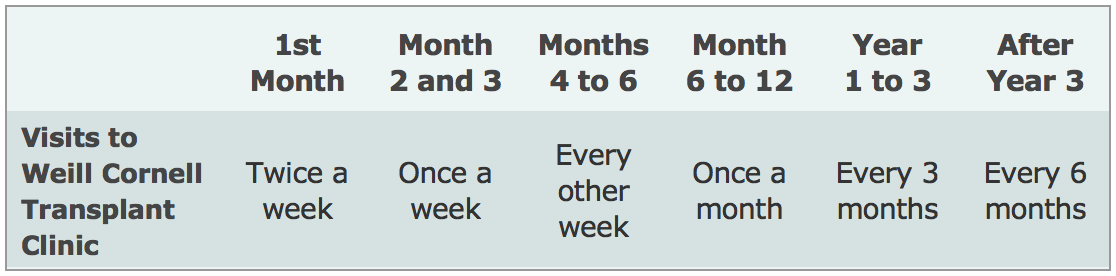

After you are discharged from the hospital, you should expect to come back to the transplant clinic two to three times a week for the first month, then weekly for the next two months, then less frequently, depending on how you are doing.

You will also be able to return to the doctor(s) who was caring for you before our transplant, such as your endocrinologist. We will work closely with your doctor to manage your transplant, and you will continue to visit our Transplant Center periodically to ensure that your pancreas is functioning well, according to the schedule below. However, more frequent visits to the transplant center may be needed depending on your post-transplant course or if you choose to participate in a research study.

What are the risks of pancreas transplantation?

There are several categories of risks that may be seen with pancreas transplantation.

The first are risks surrounding the surgery itself. These risks include side effects of general anesthesia; bleeding; blood clots; leaking or blockage where the pancreas is connected to the intestine; infection; failure of the transplanted pancreas to work; rejection of the pancreas.

Other risks come from the medications that must be taken to prevent rejection of the pancreas. These may include high blood sugar or diabetes (type 2 diabetes); high blood pressure; electrolyte imbalance; skin changes; weight gain; nausea, vomiting or diarrhea; thinning of hair. Patients taking immunosuppression are also at higher risk for developing infection and cancer, particularly skin cancer.

What is rejection?

Rejection is a normal reaction of the body to a foreign object. When a new pancreas is placed in a person's body, the body sees the transplanted organ as a threat and tries to attack it. The immune system makes antibodies to try to kill the new organ, not realizing that the transplanted pancreas is beneficial.

To allow the organ to successfully live in a new body, medications called immunosuppressants must be given to suppress the immune system from attacking the organ for as long as the transplant continues to function.

What is done to prevent rejection?

Medications must be given for the rest of the life of your transplant pancreas to fight rejection. Each person is individual, and the transplant team customizes your medication regimen to your specific needs. The anti-rejection medications most commonly used for pancreas transplant recipients include:

Intravenous medications given in the hospital at the time of transplant:

• Basiliximab (Simulect)

Oral medications taken for as long as transplant continues to function:

• Tacrolimus (Prograf) and

• Mycophenolate sodium (myfortic) or mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept)

• Prednisone

Some patients may also receive one or more of the following medications, usually when they are at higher risk for rejection due to prior transplants, prior blood transfusions, and/or pregnancy:

• Rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin (Thymoglobulin)

• Rituximab (Rituxan)

• Intravenous immune globulin (IVIG)

New anti-rejection medications are continually being studied. You may be offered the opportunity to participate in a clinical research study of a new transplant immunosuppressant or other transplant-related medication. The transplant team tailors drug regimens to meet the needs of each individual patient.

Usually several anti-rejection medications are given initially. The doses of these medications may change frequently as your response to them changes. Because anti-rejection medications affect the immune system, people who receive a transplant will be at higher risk for infection. A balance must be maintained between preventing rejection and making you susceptible to infection. Blood tests to measure the amount of medication in the body are done at follow-up visits to make sure you do not get too much or too little of the medications.

This risk of infection may be higher in the first few months after transplant because higher doses of anti-rejection medications are given during this time. In the first few months after your transplant, you will be given several medications to prevent certain types of infection.

What are the signs of rejection?

The following are some of the most common symptoms of rejection. However, each individual may experience symptoms differently. Symptoms may include:

• High blood sugar

• Elevated blood levels of amylase and lipase, two enzymes produced by the pancreas

• Pain or tenderness over the transplant pancreas

• Fever

Your transplant team will instruct you on whom to call immediately if any of these symptoms occur.

What is my long-term outlook after pancreas transplantation?

Living with a transplant is a life-long process. Medications must be given to suppress the immune system so it will not attack the transplanted organ. Other medications must be given to prevent side effects of the anti-rejection medications, such as infection. Frequent visits to and contact with the transplant team are essential. Knowing the signs of organ rejection and watching for them on a daily basis are critical.

Unfortunately, pancreas transplants do not last forever. If a transplanted pancreas fails, the decision to give a person another pancreas transplant is decided on a case-by-case basis and requires consideration of many different factors.

What happens if my pancreas fails?

If a pancreas transplant fails, the patient will need to return to managing their diabetes with insulin injections and intense blood glucose monitoring. It may be possible to receive another transplant, however, this depends on many factors such as number of previous transplants, levels of antibodies in the body, and whether the patient was adherent to their medication and follow-up schedule.