This August, Legionnaires’ disease has claimed several lives and sickened more than a hundred people across Central Harlem. But the outbreak has begun to level off, according to Acting Health Commissioner Dr. Michelle Morse, who points to the decline in new cases of the disease—a sure sign that it’s on its way out.

And there’s more good news: all 12 water cooling towers that tested positive for Legionella pneumophila—the bacteria that causes Legionnaires’ disease—have been thoroughly cleaned.

You can stay on top of what’s happening by visit the NYC Department of Health’s Legionnaires’ page here.

To clarify, the outbreak isn’t related to a building’s hot or cold water supply. That’s because a building’s plumbing system is separate from its cooling system. The residents of Central Harlem can continue to drink water, bathe, shower, cook and use their air conditioners free from worry.

However, Legionnaires’ disease is no small matter for people considered at high risk for contracting it, including:

And it’s no small matter for the loved ones of those who have died or who are severely ill.

It’s important, then, for all of us to get acquainted with Legionnaires’, the better to recognize its symptoms and seek treatment before it has a chance to upend our health.

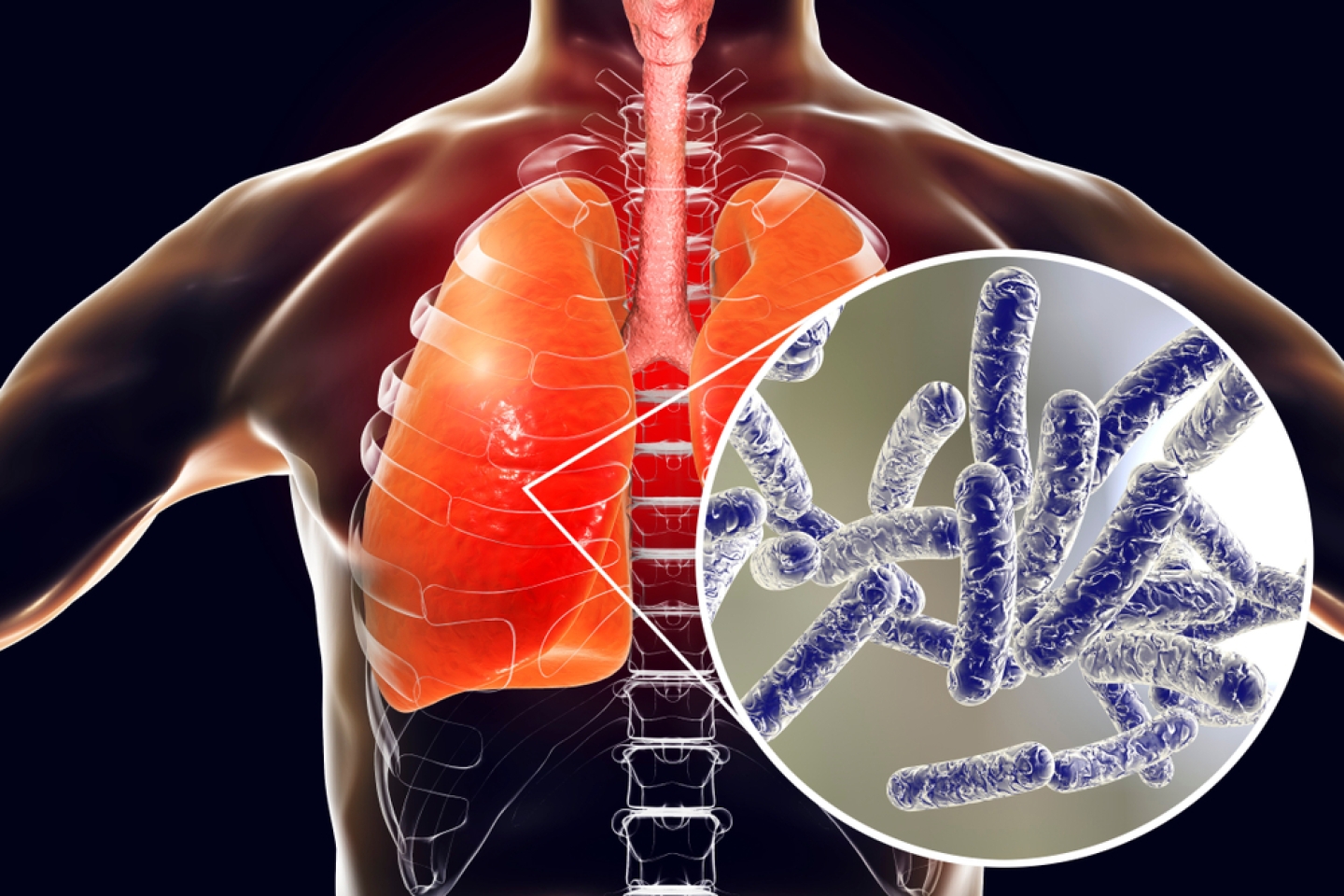

Legionnaires’ disease is a severe type of pneumonia. It can lead to hospitalization, low oxygen uptake and even respiratory failure.

The number of Legionnaires’ cases nationwide has grown slowly but steadily over the past 20 years. New York City had a major outbreak in 2015, during which at least a dozen people died, and more than 100 became ill.

While not as prevalent as other bacterial infections, Legionnaires’ disease is around, both in urban and rural areas, and it doesn’t appear to be going anywhere.

In 1976, an outbreak occurred in Philadelphia among people attending a state convention of the American Legion. That led to the name Legionnaires' disease. Later, its name was officially changed to Legionellosis, but most people, including doctors, still call it Legionnaires’ disease.

“The disease is not acquired through drinking water or transmitted from person to person,” says Dr. Matthew Simon, chief hospital epidemiologist and deputy medical director for infection prevention and control at Weill Cornell Medicine, as well as Associate Professor of Clinical Medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases and Associate Professor of Clinical Population Health Sciences. “It’s acquired through inhalation of contaminated water. Most healthy people who are exposed to the bacteria don’t get sick,” he explains.

But if you belong to one of the vulnerable groups listed above, you may “catch” the disease by inhaling mist or droplets from contaminated water in cooling towers atop buildings in the city.

Private owners are responsible for inspecting and cleaning the towers on their buildings as mandated by the City’s Department of Health. The Health Department also carries out routine inspections, and cleanups when necessary, of buildings owned by the city.

Going deeper, the city’s public health labs are currently comparing the DNA in the cultures grown from the cooling towers to the DNA in the cultures from patients. Molecular analysis of Legionella bacteria from patients and cooling tower specimens will help the NYC Health Department determine a possible match.

“The Legionella bacteria thrives in warmer water, and we see a seasonal peak in the summer and late fall, partly related to air conditioning use. That’s because building water and ventilation systems may foster conditions for the bacteria to thrive,” says Dr. Simon.

Additionally, the culpable bacteria can thrive in whirlpools, Jaccuzzis, fountains and building-wide air conditioning systems.

Its most common symptoms are:

Affected people may also experience:

Symptoms may appear within 2 to 14 days of exposure.

Dr. Simon emphasizes that most healthy people exposed to Legionella do not become ill.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the disease can be diagnosed via a urine sample or a respiratory culture, which allows a pathologist to look at mucus from the lungs.

From a public health perspective, a sputum culture will allow local or state health departments to test and match it with an environmental sample to help identify the bacteria’s source.

Legionnaires’ disease can be effectively treated with antibiotics, if diagnosed early.

If you live in a neighborhood or community where Legionnaires’ cases have been identified, and if you have flu-like symptoms, make an appointment with your primary care physician or family health provider as soon as possible. The earlier the better!

Find an infectious disease provider at Weill Cornell Medicine here.