Many of us have heard of the herpes virus—specifically HSV, the virus that causes cold sores. However, there are many other types of herpes, including chickenpox and cytomegalovirus (CMV).

CMV is an extremely common virus, and knowing about it is critical for many people, especially pregnant women and individuals living with weakened immune systems. The results of a missed CMV diagnosis can be severe, leading to birth defects in infants or pneumonia, hepatitis and more in adults.

“Up to 60% of kids at 6 years of age are positive for CMV,” says Christine Salvatore, M.D., chief of pediatric infectious diseases in the Department of Pediatrics at Weill Cornell Medicine. “And when you reach your 30s and 40s, around 80% of the population is positive. That tells you just how common this virus is.”

The impact of CMV depends on the health of the infected individual. An otherwise healthy adult may not even know they have the virus because their fully functioning immune system can fight it off without any symptoms appearing. But if the body is immunocompromised, the effects of the virus can be more intense.

“In children and adults with cancer who are undergoing chemotherapy, the immune system can become compromised,” Dr. Salvatore says. “If the body can’t properly defend itself, the manifestations of CMV can be more severe. You can have pneumonia, hepatitis, a virus in the blood called viremia, or it can go to the brain, causing encephalitis.”

The most challenging aspect of managing CMV is that most people with CMV have no symptoms and aren’t aware they’ve been infected. If a pregnant woman becomes infected, she can pass the virus to her baby during pregnancy.

In the United States, CMV is recognized as the leading infectious cause of birth defects. About one out of every 200 babies is born with a congenital CMV infection. Of these babies, around 1-in-5 will have long-term health problems, such as hearing loss, developmental and motor delays, vision loss, microcephaly and seizures. About 15% of babies with congenital CMV won’t show any signs at birth but will later develop hearing loss.

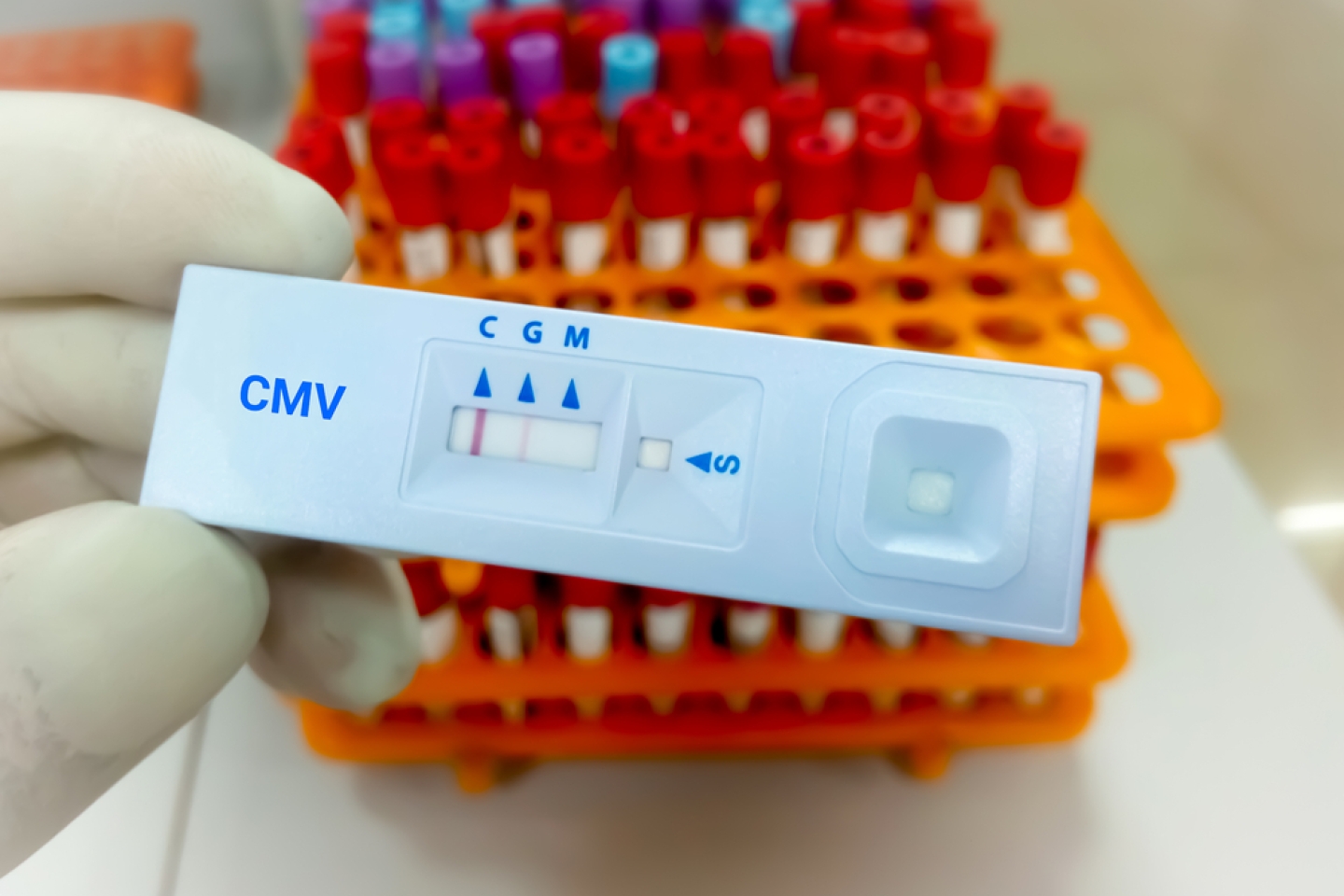

Some babies with congenital CMV infection have signs at birth, such as rash, jaundice, low birth weight and microcephaly (small head). A doctor can diagnose a congenital CMV infection by testing a newborn baby’s urine, saliva or blood. These specimens must be collected for testing within two to three weeks after the baby is born to confirm a diagnosis. If testing takes place later than three weeks following birth, distinguishing between congenital CMV infection and an infection acquired after birth is impossible.

For babies with signs of congenital CMV infection at birth, antiviral medications (such as valganciclovir) might improve hearing and developmental outcomes. Valganciclovir can have negative side effects and, so far, has only seen studies for babies with signs of congenital CMV infection. Additionally, there is a lack of reliable information regarding the effectiveness of using valganciclovir to treat infants with hearing loss.

“We need to increase awareness of the virus and increase the knowledge of how it’s transmitted, especially to expecting parents,” Dr. Salvatore says. “Overall, we want expecting parents to know that we’re here for them, ready to answer their questions and support them at every step.”

Because the majority of babies born with CMV show no signs, pediatric infectious disease specialists have been pushing for universal screenings. If a baby shows signs at birth, it prompts the health team to check for CMV. But most babies don’t get checked by default, especially if there are no symptoms.

“We’ve been saying for a long time now that instead of doing only some sectoral screening, we should start doing this screening on everybody,” Dr. Salvatore says. “And now, two states in the United States are doing it. One is Minnesota and the other is New York. Last October, by law, New York started screening every single baby born in the state. This is actually picking up a lot of the babies we would have missed otherwise. And as infectious disease specialists, we’re thrilled we’re able to help if there’s the need, or at least follow these babies in the long-term.”

Since CMV is so common and has potentially dormant symptoms, Dr. Salvatore tells her patients to focus on two important factors when it comes to CMV safety.

“If you're pregnant, have toddlers at home, or work with children, take standard precautions to reduce the transmission of CMV,” Dr. Salvatore says. “Wash your hands carefully. Don't put a pacifier in your mouth to clean it. Taking these steps could reduce the chances of babies getting an infection.”

“The second factor is many of these babies are going to be fine,” Dr. Salvatore continues, “so try not to worry too much. It is important to do a screening to get a better picture of what the baby has so we can help them avoid all the possible long-term outcomes. Just reach out when you need us and live a normal life, because many of these babies will be just fine.”

Discuss your concerns about CMV with your doctor, who can provide advice that is best tailored to your health. Find a doctor at Weill Cornell Medicine to help manage your health.