When Stephanie L. Mick, M.D., saw a beating heart during her general surgery residency at NewYork-Presbyterian, she knew that cardiac surgery was her calling.

“I was trying to decide what I wanted to specialize in within surgery, and it was getting to the point where I was at the end of my rope,” says Dr. Mick, director of robotic and minimally invasive cardiac surgery at NewYork-Presbyterian and Weill Cornell Medicine. “I was on a thoracic surgery rotation, and part of the operation included opening the pericardium for tumor resection. When I saw the heart, it was like seeing an old friend. I thought, ‘Cardiac surgery is definitely what I want to do.’”

Not only did Dr. Mick become a cardiac surgeon when there were few women in the field, she went on to become a nationally recognized expert in minimally invasive and robotic cardiac surgery. Her early training cemented her as a pioneer in robotic repair of the mitral valve — she is still one of a small number of surgeons across the country who perform it — and under her leadership, in 2024 NewYork-Presbyterian and Weill Cornell Medicine received for the second time the prestigious Mitral Valve Repair Reference Center Award from the American Heart Association and the Mitral Foundation, which recognizes superior outcomes and adherence to evidence-based guidelines with respect to mitral valve surgery.

Dr. Mick has performed over 1,000 robotic cardiac surgeries over her career and her research has helped propel the acceptance of robotic mitral valve repair.

“I love operating on something that’s so critical and central to life, and I love making a big difference in people’s lives,” says Dr. Mick. “My goal when I came to NewYork-Presbyterian was to make the robotic-surgery program a really high-quality program with high-quality outcomes. This award demonstrates how our team has been able to offer that level of care to our patients.”

In 2012, fresh out of completing her subspecialty training at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Dr. Mick’s cardiothoracic surgery career began at Cleveland Clinic. During her eight years there, she grew her expertise in mitral valve repair and helped fuel growth of robotic cardiac surgery.

“I always had an interest in the mitral valve and in minimally invasive surgery, and I wanted to learn robotics as it was the latest technological innovation at the time,” says Dr. Mick. “I started training in it when nobody knew what its future was going to be. At our surgical meetings, there used to be heated debates over whether robotic mitral valve repair was a useful and viable way of doing things. Now, it’s considered state of the art, and I was excited to be involved when it was just getting off the ground.”

Dr. Mick trained under some of the earliest experts in robotic surgery at Cleveland Clinic, building her technical expertise and conducting research that helped shape the field. In 2015, she authored one of the first and largest studies comparing use of del Nido cardioplegia versus Buckberg cardioplegia, which are solutions used to arrest and protect the heart during valve surgery. Robotic surgery is what inspired Dr. Mick’s interest in del Nido cardioplegia, as its dosing interval allows robotic surgery to proceed without the kind of frequent interruptions for redosing required in other types of cardioplegia.

The data showed that the del Nido solution, previously only used in pediatric patients, was a safe and effective alternative to the Buckberg solution (one common standard at the time) across open, minimally invasive, and robotic procedures. Establishing this safety paved the way for its use in robotic procedures, and this refinement in the conduct of these cases facilitated robotic cardiac surgery’s growth. “It was the most important study I have done,” says Dr. Mick. “It changed surgical practice all over the world and has generated significant follow-up research and discussion.”

While at the Cleveland Clinic in 2018, the robotic team, including Dr. Mick, performed an analysis on the first 1,000 consecutive cases of robotic mitral valve repair at Cleveland Clinic, demonstrating the technology’s efficacy, safety, and improvements in factors such as procedure times, transfusion times, stroke risk, and more. This data helped to establish the importance of a screening algorithm based on preoperative imaging (e.g., transthoracic echocardiography, CT angiography, and coronary imaging) to aid patient selection for robotic mitral valve surgery, a key component for success.

Dr. Mick says the collective findings from the research she was involved in helped move the needle on the perception of robotic mitral valve repair in the industry. “Cardiac surgeons are very conservative about making technical changes in their operations for good reason, because any missteps in their cases can mean life or death,” she says. “When a surgeon is trying to learn a new skill and the cost of learning new skills is potentially threatening people’s lives, it can make them nervous about adopting a whole technology. These studies consistently demonstrated excellent results over many cases, which is one of the main reasons robotic surgery is accepted now.”

In 2019, Dr. Mick was recruited to lead the robotic cardiac surgery program at NewYork-Presbyterian and Weill Cornell Medicine. “I was excited to return because I’d done my training here,” says Dr. Mick, who attended Weill Cornell Medicine for medical school and did her internship and residencies at NewYork-Presbyterian. “One of my considerations when deciding to move to another institution was ensuring that I could continue to maintain the quality of care that I was accustomed to, both inside and outside of the operating room. I was able to do that by coming to NewYork-Presbyterian and Weill Cornell Medicine. I am lucky to have a high-quality ICU and a supportive team here that routinely achieve great outcomes.”

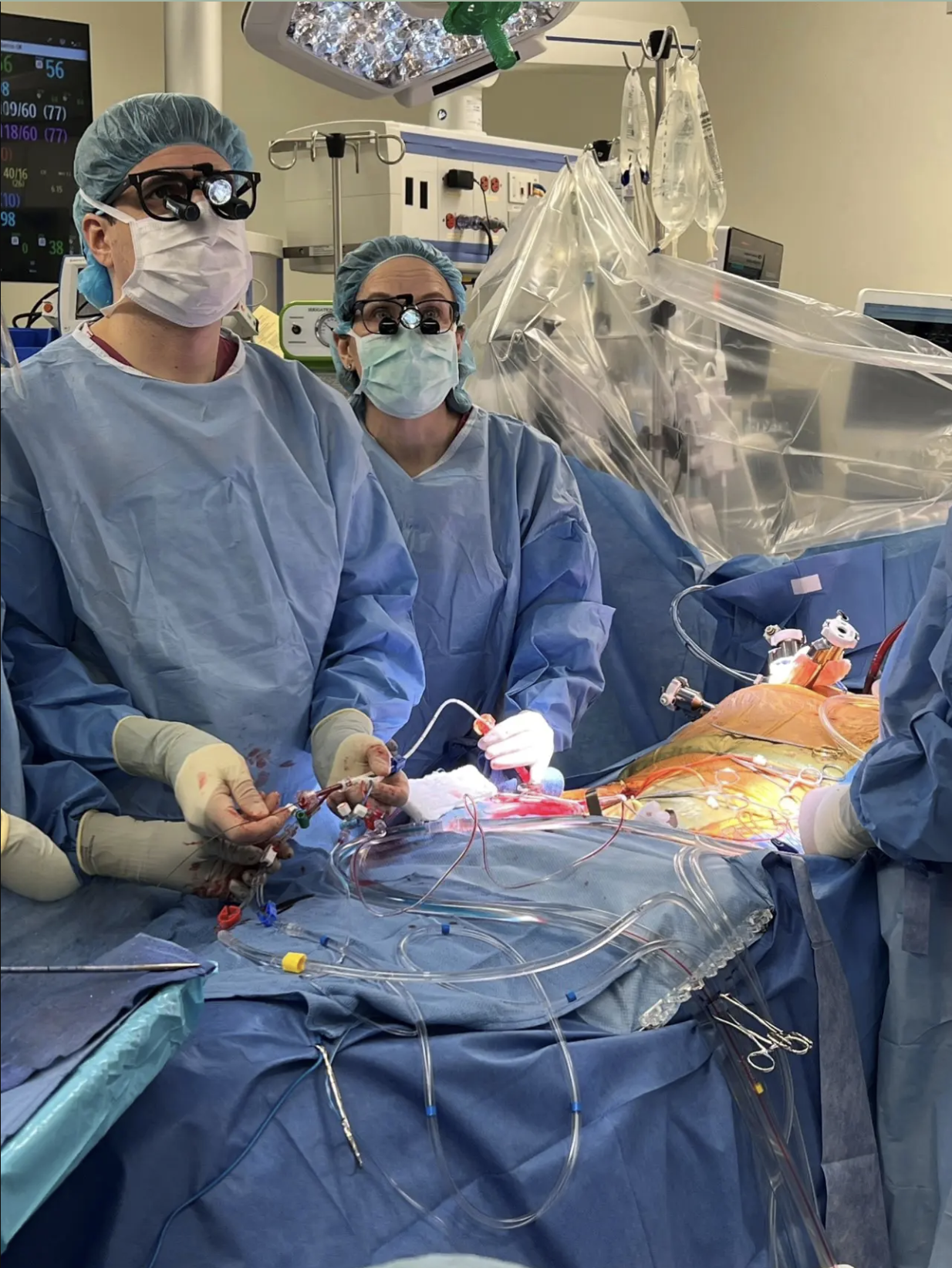

Dr. Mick (right) and a trainee perform an endoaortic balloon occlusion during robotic mitral valve surgery.

Over her career, Dr. Mick has performed over 1,000 robotic mitral valve repair procedures with excellent outcomes, as well as tricuspid valve repairs, closures of patent foramen ovales (PFO) and atrial septal defects (ASD), resections of cardiac tumors, and ablation procedures for atrial fibrillation. As an educator, she has also prioritized investigating the learning curve for teams performing robotic cardiac procedures, as the timeline to proficiency is often indicated as a barrier to adoption.

“You have to first become an expert in open surgery, which takes years, and then it takes a long time to become an expert in the robotic technology and approach,” says Dr. Mick, who stated it took about five years of performing robotic surgeries to feel completely confident she could handle any unexpected scenarios. Dr. Mick was involved in research at Cleveland Clinic that showed surgeons needed to perform 200 cases before complications, cross-clamp times, and other factors begin to level off. However, no one had ever done research on the learning curve of a new team being led by an experienced surgeon.

“I was really just curious how long it would take my team to get up to speed because they were not familiar yet with the way I work. Would it take 200 cases?” she says. The team measured both her personal learning curve in transitioning to a new program using cross-clamp times, and the team’s curve as reflected in total operating time. As expected, Dr. Mick’s learning curve was not impacted, but the team’s learning curve was surprisingly quick. “It only took 30 cases for operating time to improve and level, with excellent patient outcomes. That was reassuring and shows that building a new team is readily and certainly doable.”

The research, published in 2024, underscores the importance of the whole team working together — from surgery to anesthesia to nursing and perfusion, and beyond — when it comes to producing positive outcomes from robotic surgeries. “Particularly in the operating room and ICU, you are coordinating a team and if this is not done effectively, things can go awry,” Dr. Mick says. “When I'm at the robot, I’m looking into a console. And that means everybody in the room has to be performing even more intensively than they normally would be. The team is so insanely important, which is why I wanted to write about it.”

Dr. Mick says she’s proud of the progress she and her team have achieved over the past five years, which only stands to raise the standards of robotic surgery across the field. “Even with a new team, we have all these great outcomes — we got up to speed quickly, we have nearly 100% repair rates, we have minimal complication rates, and we’ve been recognized for our excellence,” she says. “Working with colleagues from other disciplines and building effective relationships has also not only provided synergistic benefits for myself and my colleagues, but it’s also enabled us to continue offering really high-quality surgery to our patients.”

This story first appeared on NewYork-Presbyterian's newsroom.