In the New York Times bestseller Everything Is Tuberculosis, author John Green draws attention to a horrifying fact: Over the course of human history, tuberculosis (TB) has killed more of us—approximately a billion people—than any other disease. And it continues to be the leading cause of death across the globe today, mainly in developing countries.

What makes it so lethal? Why is it still such a severe health threat, even in the 21st century? What do we actually know about this deadly disease?

In what follows, Dr. Kyu Rhee, Professor of Medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases, Professor of Microbiology and Immunology and Attending Physician at Weill Cornell Medicine—along with his colleagues—answers your FAQs. They explain the complexities of TB and what to do if you’re diagnosed with one or another form of it.

Additionally, as head of the Rhee Lab, Dr. Rhee continues to pursue research into the nature of the bacteria, Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), that causes the disease, how it spreads, and the development of new potential treatments.

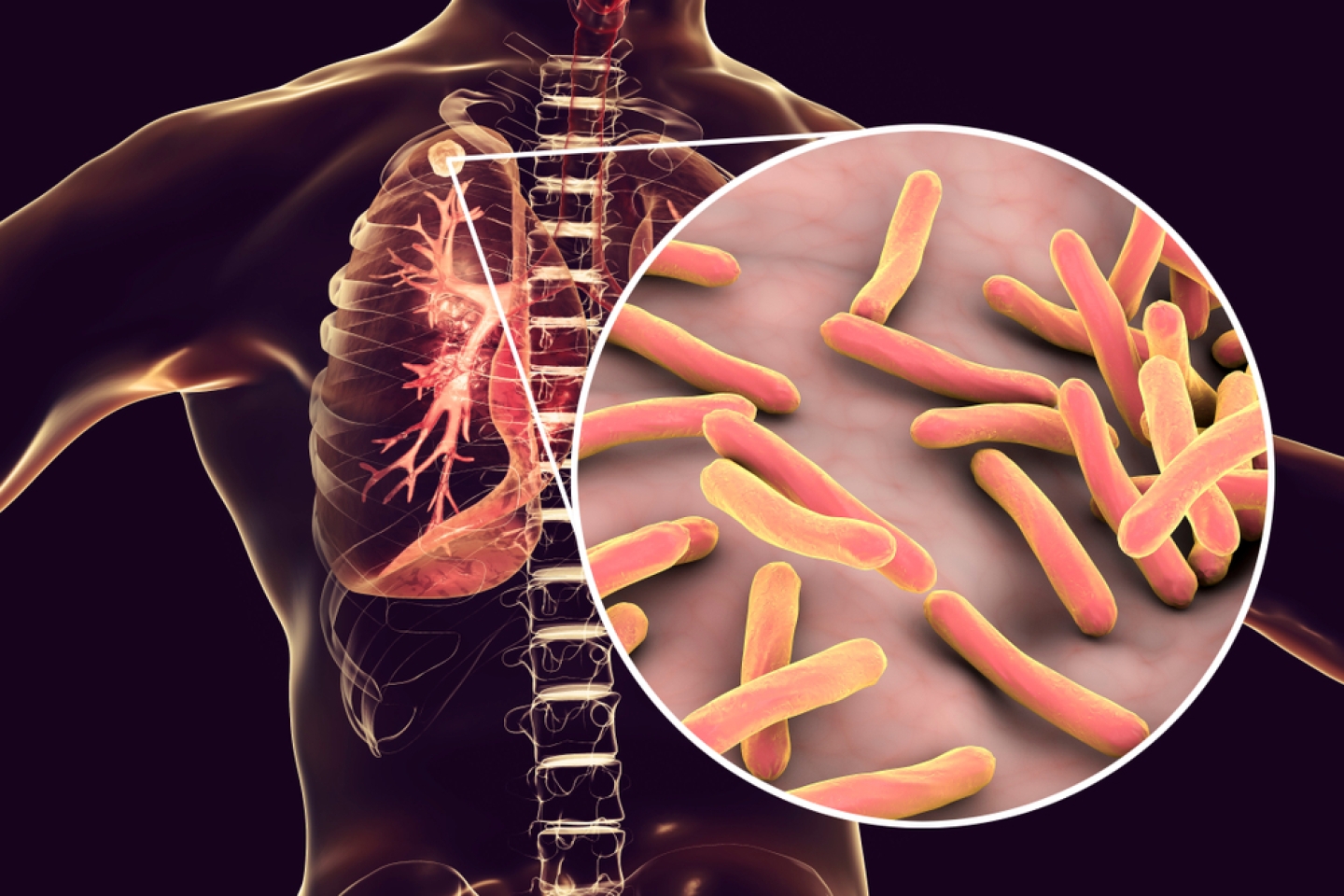

Tuberculosis is a bacterial infection caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and can affect almost any organ in the body but most commonly involves the lungs.

In cases of active TB, bacteria are rapidly replicating and causing damage. In many cases, however, Mtb infects people without making them sick, because our immune systems can contain but not eradicate it. This is considered inactive or latent infection.

“Most people exposed to Mtb can become latently infected. They don’t develop symptoms,” says Dr. Rhee, “but they remain at risk if their bodies can no longer control it. In fact, the majority of cases of active TB in adults are due to the reactivation of a latent infection.”

In most cases, TB, like measles and COVID-19, is transmitted from people with active TB via tiny, airborne particles. These are so small they can linger in the air for hours, and they can reach the innermost parts of an uninfected person’s lungs. Once there, it can establish a new infection in that individual.

The symptoms of active TB vary from patient to patient, he explains, but typically include fever, weight loss, night sweats and fatigue.

The symptoms of pulmonary TB—the most common form of active disease—include a bloody cough, chest pain and pain on breathing, in addition to the more general symptoms listed above.

“Be aware that TB can cause disease in nearly any part of the body,” Dr. Rhee says. Here are a few examples:

The biggest risk factor for TB is being exposed to another person with TB.

In the US, where TB is not particularly common, transmission tends to happen in places where there isn’t enough medical care to diagnose people with active TB, along with overcrowding, malnutrition and poor ventilation. While these risk factors may seem too unusual to worry about, TB is so contagious that even a single case can spread to as many as 15 people, establishing new cases of latent disease that can progress to active TB years later.

At a population level, the single most effective intervention to prevent TB is a public health system focused on sanitation (including adequate ventilation), hygiene, nutrition, and the ability to detect and track new cases of active TB. The recent uptick in TB cases in the U.S. is most likely a result of changes to organizations like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that form the backbone of the U.S. public health system, normally responsible for tracking cases and working with state and local agencies to prevent further spread.

Still, according to the CDC, the U.S. continues to have the lowest TB incidence and prevalence rates in the world. That means there’s little cause for worry.

“Americans shouldn’t be routinely tested,” Dr. Rhee says. “That’s because the diagnostic tests we have for TB aren’t perfect. As a result, in parts of the world where the prevalence of TB is particularly low, these tests can be falsely positive.”

Instead, screening for TB infection should only be performed in people who are at risk for the disease, including:

All that having been said, the skin test, called the purified protein derivative (PPD), is still used. However, another test—the interferon gamma release assay (IGRA)—is often used instead. The IGRA is a blood test, meaning there’s no need for the patient to come back to the office to have their results read and interpreted.

If you have symptoms of active TB, other tests designed to detect the bacteria or other specific signs of the disease may be performed, such as a phlegm culture, a biopsy of affected areas or more comprehensive imaging studies.

The first step is to see your health-care provider, who will assess what’s going on. The process may include a chest X-ray and a sputum test.

After that, says Dr. Kohta Saito, an Assistant Professor of Medicine and Assistant Attending Physician at Weill Cornell Medicine as well as an independent TB researcher who collaborates with Dr. Rhee, “have another conversation with your provider about your risk of reactivation and whether to pursue treatment with antibiotics.”

Antibiotic treatment may not always be indicated, as only a minority of patients progress to TB disease. But in the U.S., people are often tested under the assumption that they’ll benefit from antibiotics if they test positive.

All forms of TB can be treated with antibiotics, says Dr. Saito, but treatment tends to be longer and more complicated than for virtually any other bacterial infection.

“Unfortunately,” he says, “the sheer length of these regimens increases the risk of significant side effects. For people being treated for latent TB infection, this is a challenge, as they experience the side effects of medications they’re taking to prevent a disease they may not go on to develop.”

He explains that people being treated for active TB often start to feel better long before they’re cured, and similarly begin to experience more side effects than relief from treatment.

In both cases, he adds, “this makes it difficult for people to complete their course of treatment, increasing the chances of treatment failure and the potential for antibiotic resistance.”

Mtb, the bacteria that causes TB, may carry mutations that make it resistant to first-line antibiotics. Drug resistance can make the disease much more difficult to treat. In the U.S., there were 589 cases of TB that were resistant to at least one front-line drug in 2023, according to the CDC.

TB is so contagious that even a single case of drug-resistant TB poses a threat not only to that individual but to the entire community where they reside.

“The only vaccine for TB is one that’s given at birth and protects against a specific form of TB in infants and young children,” says Dr. Christopher Brown, another colleague of Dr. Rhee’s who is also an Assistant Professor of Medicine and Assistant Attending Physician at Weill Cornell Medicine. “But the vaccine provides no consistent or reliable activity against pulmonary TB, which is the most common form of TB in adults.”

Most important of all, see your doctor if you’ve been exposed to TB, or if you experience any of the symptoms described above.

Make an appointment with an infectious disease specialist at Weill Cornell Medicine.