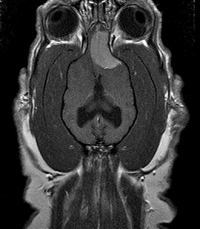

An axial view (from above) of a standard poodle with a brain tumor. The tumor was successfully removed using open surgery at the Animal Medical Center in New York.

A new partnership between the Weill Cornell Medicine Brain and Spine Center and the Animal Medical Center (AMC) in New York will help advance minimally invasive brain tumor surgery in dogs, and may also teach us a few things about brain tumors in humans.

Dr. Philip Stieg, neurosurgeon-in-chief of Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian and chair of the Weill Cornell Medicine Brain and Spine Center, and Dr. Chad West, the head of the neurology/neurosurgery service at AMC, will collaborate on this new program, which will help veterinary neurosurgeons develop minimally invasive and endoscopic surgical techniques for dogs diagnosed with brain tumors. The program is being funded by a generous grant from Kathrine and William Rayner.

A dog can’t tell you when it has a headache or feels dizzy, of course, so the first sign of a brain tumor in an older dog is usually the onset of seizures. “Idiopathic epilepsy – meaning recurrent seizures without structural brain disease – is not uncommon in younger dogs,” says Dr. West, “but when an older dog presents with an acute seizure disorder, brain tumors must be considered as a primary differential diagnosis.” The good news is that if a veterinary neurosurgeon canremove the tumor, the dog’s life can be extended by several years.

This Shiba Inu had a brain tumor that was successfully removed using open surgery.

Unfortunately, open surgery to remove a brain tumor requires five or more days of post-surgical hospitalization, which many pet owners can’t afford. A minimally invasive option that reduces hospitalization stay would allow more dogs to have surgery and enjoy those extra years of life.

“Surgery is sometimes an option,” says Dr. West, “but owners often elect radiation instead of open surgery. We’d love to have a minimally invasive option to offer, but brain tumors in dogs are extremely complicated and we haven’t yet developed the skills to offer endoscopic surgery.”

Canine brain tumors can be even more complex than those in humans, Dr. West notes. “Dog brains are all so different based on breed,” he says. “Cats all have the same basic anatomy, and no matter what a human looks like on the outside we all have pretty much the same head. But from one breed to another, dog brains are dramatically different.”

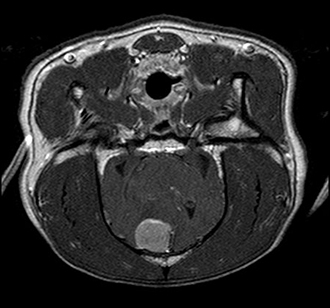

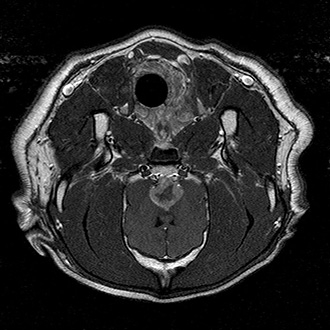

A skull base tumor like the one this Labrador Retriever had, however, requires endoscopic surgery, which isn't possible yet in dogs.

Further complicating surgery to remove a brain tumor in a dog are the surgical approaches necessary to remove the mass. Dogs (and cats) typically present to a veterinary neurologist much further along in their disease course than a person would, because subtle signs suggestive of intracranial disease may go undetected. That means that brain tumors in veterinary patients are often larger than those in humans. A large surgical approach is currently necessary to access these large tumors and is often limited by the ability to interfere with venous sinuses that drain blood from the brain. Minimally invasive approaches with neuroendoscopy would allow for more pets to be surgical candidates.

Dr. Stieg is delighted to be able to offer a new surgical option for dogs, but he also sees an opportunity for learning more about brain tumor biology in humans. “We have learned so much about brain tumors over the past two decades, but there’s still a lot we don’t know. If it’s possible to gain some new insights into brain tumors by studying animals, then that would make this project win/win.”

For example, the most common type of brain tumor is a meningioma, a tumor near the surface of the brain that’s usually quite amenable to surgical resection. In cats, as in humans, meningiomas tend to have clear margins and can be removed in relatively straightforward surgical procedures. In dogs, however, meningiomas tend to be infiltrative, without clear borders. No one knows exactly why that is, but since infiltrative tumors are the most resistant to treatment in humans, whatever we can learn from dogs may provide clues to how and why tumors infiltrate human brains.

This domestic short-haired cat had a feline meningioma that was successfully removed using open surgery.

More complex than a meningioma is a pineal parenchymal tumor, which lies deep in the brain and is less accessible to surgeons. This tumor raises interesting questions about the variation in brain tumors by breed. “Flat-faced dogs like bulldogs get more parenchymal tumors,” says Dr. West. “Dogs with long snouts, like German shepherds and Labs, tend to get more surface tumors.” Again, it is unknown why head shape would affect the type of tumor that develops or what insight that might bring to the study of human brain tumors.

Dr. West says he’s looking forward to acquiring the skills he and his team need to be able to offer minimally invasive and endoscopic surgery to dog owners. “We just don’t have enough experience with this, no ability to study it. And until now we’ve had limited ability to learn the procedures. Having the grant makes it possible, but the funding is just the first piece. We also need the training, and that’s what the expert neurosurgeons at Weill Cornell Medicine bring to us.”