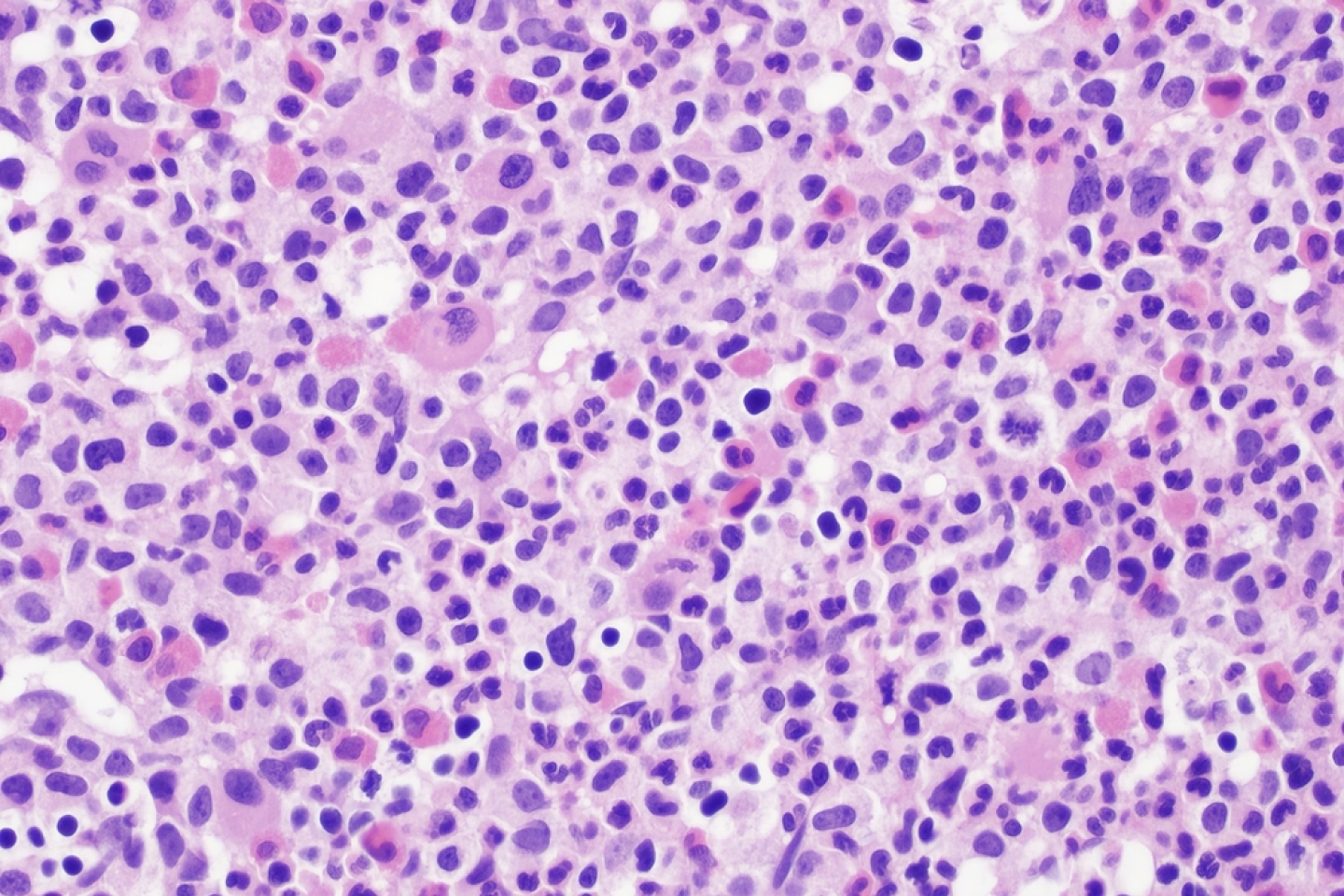

Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) are cancers of the blood and bone marrow. They start when something goes awry with hematopoietic stem cells—immature cells that can develop into any type of blood cell. Myeloid cells, also found in the bone marrow, can develop abnormalities as well. As cancerous cells tend to do, the affected blood cells proliferate, crowding out normal cells.

Broadly, MPNs are grouped as follows:

These cancers are classified based on blood counts, genetic and molecular tests and bone marrow analysis according to criteria specified by the World Health Organization (WHO).

In contrast to acute leukemia, MPNs progress more slowly. Symptoms may take months or even years to appear.

According to National Cancer Institute data from 2019, roughly 300,000 people in the U.S. have one of the classical MPNs, and CML affects approximately 70,000 people.

To help demystify these complex cancers, Dr. Ghaith Abu-Zeinah, an assistant professor of medicine in the Department of Hematology and Oncology at Weill Cornell Medicine, responds to frequently asked questions below.

The subtypes have different sets of symptoms, and the results of laboratory tests show differences as well.

For instance, an enlarged spleen is more common in PMF than in other MPNs. The so-called classical MPNs—ET, PV and PMF—carry a higher risk of clotting and cardiovascular complications, such as a heart attack or stroke, than other MPNs or than other blood cancers generally. MPN patients should be carefully monitored to prevent these complications.

The causes of these cancers remain unknown, but they may be linked to environmental exposures such as to smoking, earlier chemotherapy or immunosuppressive drugs. MPNs may also be rooted in family genetics.

Often, I see asymptomatic patients who have been found to have abnormal blood counts during a routine physical exam or from a blood draw for other reasons. Others may report non-specific symptoms such as fatigue, low appetite, involuntary weight loss and night sweats, or more specific ones such as:

We diagnose MPNs based on blood counts, bone marrow biopsy findings and other laboratory tests including gene mutation analysis. Signs and symptoms observed during a physical exam aren’t enough for a diagnosis, as these can mimic other blood cancers or even non-malignant conditions.

We tailor the treatment to the MPN subtype. Treatments are also dependent on the individual patient’s risk profile and prognosis. Each subtype is associated with a different set of biologic and molecular “drivers” that require different targeted treatments.

For example, in CML, oral tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI), such as imatinib (Gleevec), are effective in suppressing the faulty genetic signaling that the cancer cells rely on to spread the disease. Taken in tablet form, these drugs have been successful in managing CML and other types of cancer.

The classical MPNs are generally treated with cell count-lowering (cytoreductive) drugs and anti-clotting medication. Cytoreductive drugs include interferon alfa and hydroxyurea. Treatment with interferon alfa has been pioneered at Weill Cornell and has shown promise in preventing disease progression and prolonging survival in some MPN patients. With regular monitoring and treatment, the majority of patients with PV and ET can lead long and active lives.

About 15 percent of people with PV, as well as a small number of those with ET, may develop myelofibrosis, the most serious type of MPN, at 10 years after diagnosis. Myelofibrosis is a complex disease that requires individualized treatment, as symptoms and severity vary from patient to patient. For myelofibrosis patients, a hematopoietic stem cell transplant offers a potential cure.

In some cases, MPNs may progress to an aggressive type of leukemia, most commonly acute myeloid leukemia (AML). For these patients, as with myelofibrosis patients, a hematopoietic stem cell transplant may represent a cure.

Several clinical trials are being conducted to develop novel drugs and drug combinations, which, we hope, will result in effective treatments or even a cure down the road.

If you or a loved one has an MPN, learn more about patient care and research at Weill Cornell Medicine’s Richard T. Silver M.D. Myeloproliferative Neoplasms Center.